Using Visual Thinking Strategies in Dance Curriculum by Julie Lemberger

By NYPL Staff

August 2, 2018

The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

The following post was written by Julie Lemberger, a 2017-2018 Jerome Robbins Dance Research Fellow. Her project focused on comparing the professional lives and photography of Martha Swope, who documented theater, dance, and film for more than 50 years, and Jerome Robbins, who documented more casual moments in the same performance spaces. Julie has been photographing dance in New York City since the 1980s, when she was a dancer herself.

Continuing to evolve, Julie is now a professional educator, teaching how photography can be used as a tool for inquiry. She takes her teaching methods one step further, with the embodiment of what people are viewing in the photograph.

Turn the page and it’s six months since my presentation as a Jerome Robbins Dance Research Fellow, and one year since I began my investigation of Martha Swope and Jerome Robbins’ love of dance and photography. What have I been up to, why the absence from what would have been a natural progression towards making a book, blog, or journal? Well, as one of the junior (in academic accomplishments, not actual years) fellows among my esteemed cohorts, I still had the task of completing my course work toward earning the degree of Masters of Dance Education at Hunter College in the Arnhold Graduate Dance Education Program that I had been working on for three years prior to the fellowship.

The day after the presentation began the first of 12 weeks of student teaching in a New York City public school. The practicum at Hunter College’s School of Education is for budding dance educators to get experience teaching elementary school, and middle or high school students, and to be eligible and receive the pre-K through 12th grade license, provided all appropriate tests are passed. So I went from research scholar to elementary school dance teacher overnight!

I started my journey in an elementary school. As a student teacher, I was supported by the master teacher, or the cooperating teacher, Catherine Gallant. She is a recognized choreographer, scholar, and interpreter of Isadora Duncan’s dances; however, in her classroom, she teaches all manner of dancing styles and creative movement that gets her students moving and thinking creatively simultaneously. While I was there, during the first six weeks of my 12-week apprenticeship, I witnessed her teach pre-K to fifth graders dance explorations with themes including how lions move, pounce, and roar; improvising to Saint-Saëns’ "Carnival of the Animals, Royal March of the Lions;" teaching the work of Remy Charlip, including his children’s stories and "Air Mail Dances," and taking the journey of Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad with the students. The older students, fourth and fifth graders, got the opportunity to work with professional dancers from the Jose Limon Company and a ballroom dance education program.

The school was small enough that every student had a dance class once a week. After a while, I became somewhat familiar with every student, as I participated in every class, observing and assisting the cooperating teacher in action. After about two weeks of watching lessons wind down and new ones begin, the time came for me to present my unit of study or learning segment. With the way the schedule came together and the complexity of my lesson plans, as I described my idea to Catherine, she decided a third grade class would engage in my topic. She felt the curriculum wouldn’t be too difficult and the class wouldn’t be too rambunctious to manage.

She introduced me to 30 eight- and nine-year-olds, and though I had never worked with this exact population, I have children of my own who were once eight and nine years old, so I had an idea about what these students might be able to accomplish. Also, this group of students, who had taken dance class at least once per week since they were in pre-Kindergarten at age four, were well-versed in dance class protocol.

As I was decompressing from my research at the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, I could think of nothing else but dance and photography as it related to Jerome Robbins and Martha Swope, especially the documentation of the play and film of West Side Story. The idea for the lesson was to present a few, randomly selected Martha Swope photographs of the original 1957 rehearsals, and use them as entry points into observing dance in stop-motion, and simultaneously discussing Jerome Robbins’ choreography.

I got the idea from a presentation I’d seen and photographed at the 92nd Street Y by former Martha Graham Company dancer, Kim Jones, who is now making a name for herself as a dance scholar and re-imaginer of lost historic dances. When I spoke to Jones, she mentioned using Barbara Morgan’s photographs of Martha Graham in Imperial Gesture, program notes, and a performance review to re-imagine a dance that was lost from the Graham repertory. It was as if she were a dance archeologist or detective, piecing clues together of a bygone era in order to unearth and reveal history, and pay homage to the original.

I was struck by the significance dance photography had in her investigation. The photographic image preserved a moment in time and informed the future, giving one the opportunity to create something new. As a dance photographer, this validated the endurance of my work.

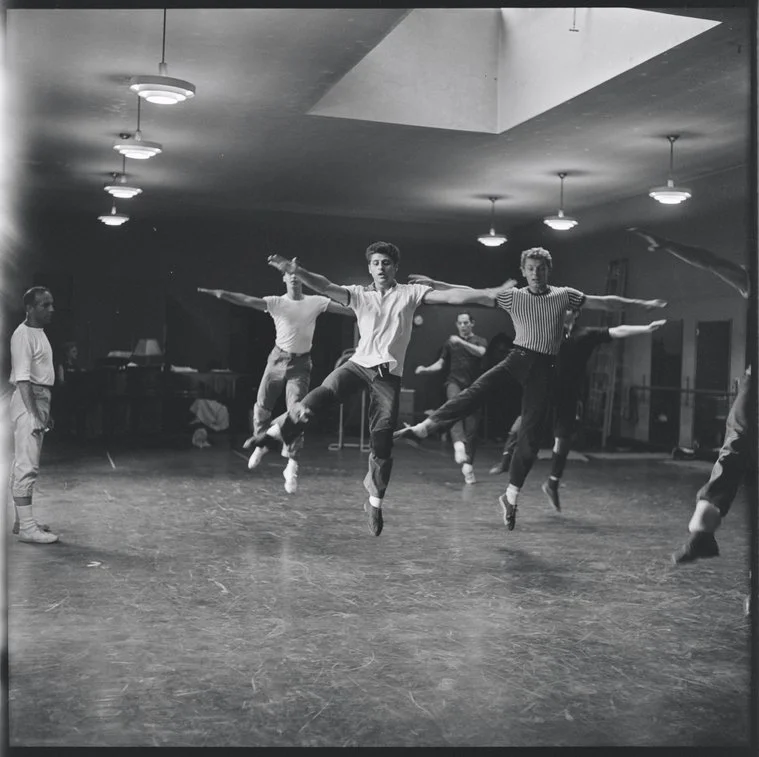

Dancers in rehearsal (men on point) for the stage production West Side Story, 1957. NYPL Digital Collections, Image ID: 56914765

In education, just like at any cocktail party, you need a good segue to transition from one unit of study or topic to another, so that students can connect content, and so the new unit does not come from nowhere. Prior to my teaching, these third graders had completed and performed a dance based on Rainbow Crow, an adapted story from the Lanape nation of Native Americans, on their school auditorium stage. They wore simple costumes and used basic props, and I photographed and helped backstage as needed. As an introduction to my first lesson, I began with a question-and-answer session about jobs or tasks they may have noticed during their performance. Students answered: dancer, choreographer, stage crew (to pull the curtain), lighting and costumes crew, and finally, photographer and videographer.

In a brief warm-up, I included some dance gestures that I had culled from the photographs. Catherine suggested I stick to a single gesture, so they could master it, before going on to another. We decided on tendu a la seconde that moved forward in space. I derived the tendu gesture from the picture of the characters the Jets, rehearsing the "Cool" dance number, though it wasn't until after the warm-up that we began to look at the photographs.

These students were adept at speaking and making connections. They saw the face-to-face action as: fighting, action, running around, and they pointed out the facts: male and female, in costumes of dresses, skirts and shirts.

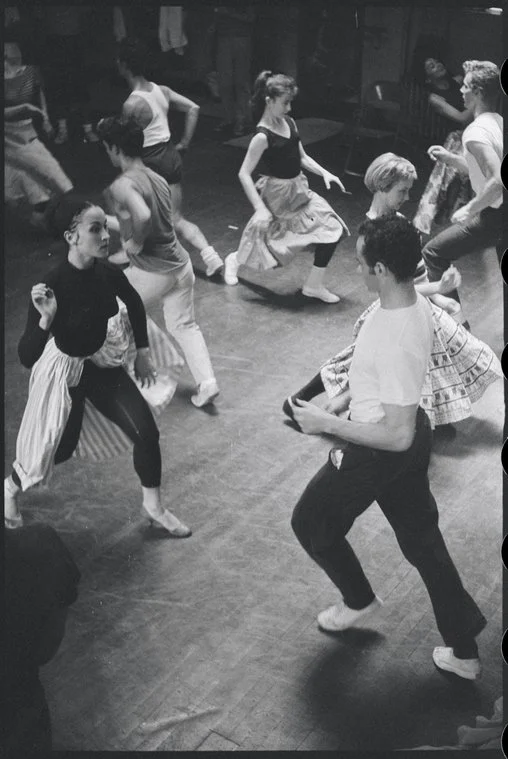

Chita Rivera, Ken LeRoy, and dancers in rehearsal for the stage production West Side Story, 1957. NYPL Digital Collections, Image ID: 56917652

One student said it looks like a tableau! A word that I had no idea was on the minds of third graders!

From here, the lessons took an unexpected turn. Now I could use the term "tableau" fluently with the class, as a way to describe patterns of movement in a photograph. As the student described, a tableau is "frozen movement, like a picture." Instantly linking pictures and movement together, just like photography of dance!

Curiously, another student noticed that, for him, the "hand looks like a skull." This statement sparked a discussion about the artists’ intention or, perhaps, it was unintentional, and the way the light or the angle it was photographed created what seems to be a "skull-like" hand gesture. This became a teaching moment about what artists, choreographers, dancers, and photographers do intentionally, or on purpose, and what happens unintentionally, by accident.

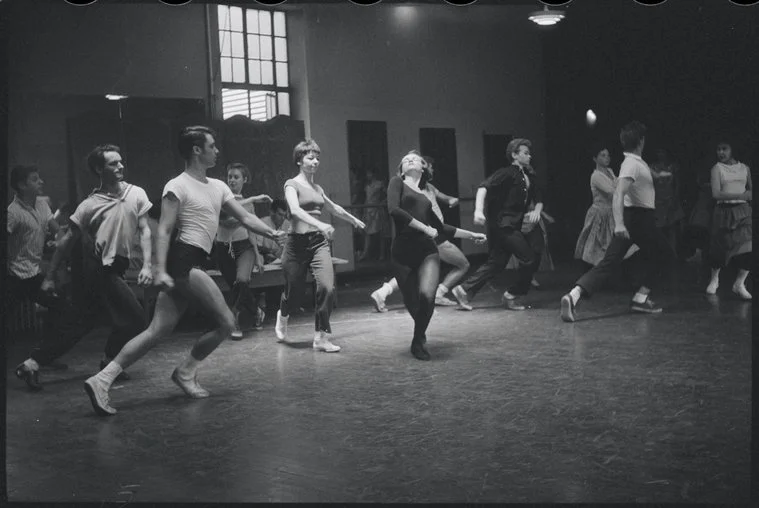

Next, we looked at this photo of Chita Rivera, Ken LeRoy, and other dancers rehearsing for West Side Story. With this photo, their response was more factual-based, saying, "someone is in the middle," "people are dancing on their 'tippy toes,'" "it is in white and black," "they have different shoes on: sneakers, high heels," and "a man is wearing trunks (initially they called it a bathing suit)." I let them know the photograph was taken in the summertime in August, and I pointed out that the window was open, and it might’ve been hot that day. Lastly, they noticed the photograph was "taken a long time ago." I found it interesting what they noticed.

Dancers in rehearsal for the stage production West Side Story, 1957. NYPL Digital Collections, Image ID: 56917657

The next session, a week later, we did not dance, but only looked, discussed and responded to the photographs, all seven of them. After a brief review about what we saw, I split up the 30 students into small groups, each to analyze and question a photograph.

The students wondered what was going on in the photographs and came up with a series of questions about the photos: What were the people doing? What song were they dancing to? Is this a rehearsal or a recital? Why are they wearing only black and white clothes?

They noticed the photographs were all taken in the same room; where was it taken? Who were the people? By the third session, the facts about the photographs were revealed. It is curious, though, that they never wondered who the photographer was. That did not stop me from letting them know.

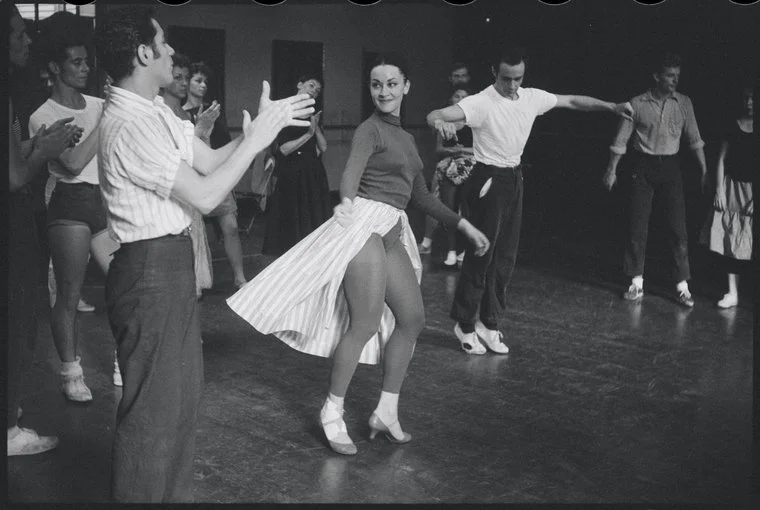

Chita Rivera and cast in rehearsal for the stage production West Side Story, 1957. NYPL Digital Collections, Image ID: 56917566

So, armed with some facts about the photographs, we got started on the next task: to animate the pictures and create a dance / dance sentence (a fragment of a dance that, like a sentence, has a beginning, middle, and an end). I instructed them, with Catherine’s advice, to create a worksheet that specifically asks for four action words found in the photographs, and then use those actions in the dance sentence. The action words put the picture in motion. I put in a caveat to make a tableau that resembles their assigned photograph.

In groups—this time different groupings from the previous activity—the students examined details in the photographs and wrote the actions they think had occurred. The action words were: half turn, (this group is experienced, and wrote the kind of turn they intended), look up, run, and walk. They chose to begin and end their dance in a tableau.

The students began rehearsing their dances, using pictures and words to inform their movements. By the end of the fourth lesson, two groups volunteered to show their rough sketch dance.

Unfortunately, I had to leave the elementary school after this lesson to go to the high school and begin anew. I had initially hoped to bring this lesson to the high school students. I had wanted to find out what a more sophisticated bunch could come up with but, unfortunately, time did not allow it and I ended up doing a completely different project.

I did return to the elementary school, however, and went over the last lesson again. With two months in between, these third graders were able to pick up the work where we left off, without much review. They even remembered their dances. My cooperating teacher, Catherine, was happily surprised too; she said the power of the photographs helped to seal and solidify the information in their minds and, therefore, they could happily pick up and continue where they left off. The third graders responded well to the information and the photography, and were able literally to run with it, as they embodied dance history, looking back and moving forward.